The Black Banking Empire of Jesse Binga

During segregation, black homeowners and small businesspeople often struggled to obtain loans from white-owned banks. Jesse Binga saw that demand and started one of the nation’s first black-owned banks.

Born in Detroit on April 10, 1865, four days before President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, Binga was one of ten children. His father, William W. Binga, was a barber, at the time an important job for upwardly mobile freedpeople. His mother, Adelphia Lewis Binga, was a real estate entrepreneur in Detroit and Rochester.

Adelphia was a major inspiration to Binga. She was a housing developer who built “Binga rows,” transitional homes built for emancipated slaves migrating North. As a young man, Jesse dropped out of high school and began assisting his mother with rent collection. He later relocated to the Seattle/Tacoma, Washington area and then Oakland, California to pursue a career, like his father, as a barber.

Binga was then hired as a Pullman Porter, saving up money to acquire property in Pocatello, Idaho, which he then profitably sold. In 1893, Binga settled in Chicago after attending that year’s astonishing World’s Fair. Chicago was a place for strivers and dreamers like Binga. With no more than $10.00 to his name, he began dabbling in real estate ventures, purchasing and repairing dilapidated buildings with the aim of renting them out.

When Chicago’s white-owned McCarthy Bank failed in 1907, Binga used some of growing financial wealth to purchase the building and to charter his own bank as a private credit institution. He gave it the eponymous name, Binga Bank.

A pivotal point in Binga’s life was his marriage in 1912 to Eudora Johnson, who was from one of Chicago’s wealthiest black families. The wedding, considered the most lavish held in the city that year, symbolized Binga’s growing reputation nationwide. It is reported that prominent black educator Booker T. Washington sent a note of congratulations to the newlyweds.

Eudora was the daughter of gambling king John “Mushmouth” Johnson, owner of a well-known local saloon. She reportedly had inherited over $200,000 in 1907 from her father (worth an estimated $5,913,787.23 today). This money was merged with Binga’s bank capitalization, making it the biggest bank among Chicago’s Black Belt communities.

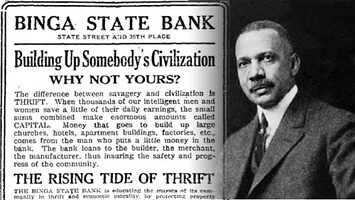

With Chicago’s population explosion, Binga State Bank was in full swing in the 1920s. Within a few short years the bank had deposits of $1.3 million (worth an estimated $37,250,762.89 today).

Adding to his portfolio, Binga acquired several South Side Chicago properties. As black transplants from the Deep South continued to flood into the area, the border of the Black Belt expanded into historically white neighborhoods. With white residents fleeing these areas for outlying neighborhoods–a foreshadowing of post-World War Two suburban white flight–Binga served as the de facto broker between white sellers and black buyers.

Over time, he became the city’s top real estate broker, a distinction that he continued to hold for the next twenty years. Due to discriminatory housing practices, blacks in Chicago faced barriers to financing for homes since white-owned banks were reluctant to lend to black families. It is here where Binga recognized that he could arbitrage racism for profit while helping black families buy homes.

Binga’s growing prominence in Chicago, however, particularly through his efforts to move black residents into previously white neighborhoods, drew the ire of many whites. His South Side home was bombed seven times over a two-year period beginning around the time of the 1919 Chicago Race Riots.

Every time there were explosions, offers would pour in from those desiring to purchase his home. Yet he refused, opting to rebuild and remain. He paid for a 24-hour security guard for months at a time and even offered a $1,000 reward for the conviction of the bombers. But there were never any arrests.

His businesses were also plagued with repeated bombings. But the biggest threat to his banking empire was the growing competition posed by other black bankers. Seeing state regulation as means to mitigate these competitive winds, Binga, along with several prominent white bankers, successfully lobbied for the prohibition of private banks.

As a result, all banks had to possess state or federal charters along with at least $100,000 in capital. Binga Bank, renamed Binga State Bank, was the only Black Belt bank able to meet that threshold.

In 1926, Binga acquired property on the northwest corner of 35th and State Street in Chicago, where he built a new $120,000 structure–the most expensive building in the district–for his newly chartered bank. Replete with marble and bronze, the rich exterior architecture caught pedestrians’ eyes. Moreover, the interior featured walnut paneling and a strikingly massive steel vault door.

Binga’s bank staff included highly educated, skilled black professionals from top tier academic institutions like the University of Chicago, the University of Michigan, and Oberlin College. With a panopticonic office view, Binga sat behind a massive glass window and marble desk that overlooked the public lobby area.

To accommodate his growing fortune, Binga purchased more property at that location and had an even grander structure erected. Known as the Binga Arcade, this five-story state-of-the art office building housed the entire Binga empire as well as other black-owned businesses.

In the ensuing years and with his meteoric rise in standing among Black Chicagoans, Binga emerged as a leading symbol of black capitalism and economic hope. He became a weekly columnist covering business and real estate for the prominent black newspaper The Chicago Defender. He also published a book entitled Certain Sayings of Jesse Binga, filled with his business decisions and life wisdom.

Binga also established the Associated Business Club, where black entrepreneurs could network and listen to lectures from high profile business owners in Chicago of all races. His ongoing philanthropic interests included donations to the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) as well as a number of historical black colleges including Fisk, Howard, and Atlanta University.

In 1929, at the apogee of his successful rise, Binga, now in his 60s, began seeking funding for a second bank, this one with a federal charter. He purchased additional property in the area of his current bank and sold shares in the new banking enterprise to investors.

The following year, however, his banking fortunes fell as the Great Depression began with a stock market crash and bank runs. By the summer of 1930, the bank’s cash reserves had dwindled, leading to a suspension of lending activities. Binga dipped into his own pocket, using much of his own personal fortune in order to remain afloat. This proved futile.

On July 31, 1930, bank auditors from the state shuttered Binga State Bank, pointing to the institution’s insolvency and accounting irregularities. As this shocking news rippled throughout the city, scores of concerned depositors began congregating at the main banking locations under the careful watch of two 24-hour policemen.

Brewing behind the scenes was a criminal case against Binga, the result of an audit that identified some missing funds. Authorities agreed to allow the bank’s board of directors a few days to raise the necessary funds, to which the board agreed on the condition that Binga step down from his role. He refused to do so.

In a last-ditch effort, the Chicago Clearing House, of which Binga State Bank was a member, met to determine whether to provide funds for the bank to reopen. The members, however, were not keen to take that risk due to the embezzlement rumors.

By the fall of 1930, the fate of Binga State Bank had been sealed with thousands of depositor’s savings completely gone. Binga was forced to declare bankruptcy and was relentlessly pursued by creditors. Even his wife, Eudora, turned on him, pursuing legal action and charging him with neglect of the family’s affairs. She asked the court to appoint a conservator to provide oversight over what little money remained.

In April, 1931 Binga was formally charged with embezzlement tied to $39,000 in pledges for the proposed national bank that had never opened. The trial resulted in a hung jury and the judge decreed a mistrial.

A second trial was initiated by the state’s attorney. In November 1933, Binga was sentenced to serve up to ten years in state prison. He remained free, however, awaiting an appeal to the Illinois Supreme Court, which was later denied. As a result, at age 70 Binga entered Joliet prison in April of 1935. Over a year later at his parole hearing, one of the nation’s most prominent attorneys, Clarence Darrow, appeared on Binga’s behalf, saying in court:

I have known Binga for thirty years and he is a man of fine character. He lost a fortune trying to keep his bank open.

While this appeal was denied, his next parole hearing a couple of years later was successful. At that hearing, tens of thousands of signatures from Chicago residents were presented in support of Binga’s release. Among the signatories were depositors who were themselves bankrupted due to the failure of Binga State Bank.

After his release, Binga returned to his South Side Chicago home. Broke and in poor health, Binga nevertheless was able to keep his creditors at bay and by working as a janitor at a local church. He died in 1950 without sufficient funds to inscribe his name on the family’s Oak Woods Cemetery headstone.

Former Chicago Sun-Times Editor-in-Chief Don Hayner, author of Binga: The Rise and Fall of Chicago’s First Black Banker, says that it was only after “thousands and thousands of hours” of his own research on Jesse Binga that he realized how much of an icon he was to Chicago and banking history.

What was shocking to me was that his story had never really been told. So my natural curiosity then went from there.

Continues Hayner:

He was a self-made man. He was self-educated too but he was smart naturally. I mean he was great with numbers from what I understood and could tabulate quickly and was often mentioned for that. He was a great negotiator, a hard negotiator.

Hayner notes that Binga’s vocal public persona predictably made him a target for white hatred, but he never backed down even as trouble continued to find him. He concludes:

In a way, I think this book is a message to the white community about entrepreneurs and Black entrepreneurs and the obstacles that at times they run into that white entrepreneurs don’t. And I think that’s a good message.

Sources

Hayner, Donald. Binga: The Rise and Fall of Chicago’s First Black Banker, Northwestern University Press, 2019

Evans, Maxwell. “Jesse Binga, Chicago’s First Black Banker Who Refused To Let Bombings Stop His Ambition, Profiled In New Book,” Block Club Chicago, December 4, 2019

Goodloe, Trevor. “Jesse Binga (1865-1920),” Black Past, March 23, 2009.