Searles and Klein explore the extent to which Hume and Smith were proto-Darwinians.

Speciation is, for the case of humans, the descent of homo sapiens from older species. The idea is that some organisms which can produce new, fertile offspring—and, hence, are a species—mutate over time into a population which is distinct in that its members then cannot reproduce with members of the older species. A new species has emerged. Human nature has a history.

A belief in speciation does not imply a rejection of theism and divine providence. One may see speciation as part of God’s means of creating man in His image. The present authors see no tension between theism and speciation—both/and is eminently reasonable.

Yet, in centuries past, both/and has been challenging, and it is no great surprise that Christendom would have suppressed the idea of speciation.

The idea is older than most people today realize. For example, Ronald Coase,[i] in his article “Adam Smith’s View of Man,” embraced Smith’s view of man, but with one supposed modification: Smith’s affirmation of divine providence may now, thanks to improved scientific understanding, be replaced by evolution, especially the principle of natural selection. “We now know, what Adam Smith could not,” says Coase, namely, that human nature evolved from other species. Coase adds: “It was David Hume’s view, and presumably also Smith’s, that human nature is revealed as being much the same in all recorded history.”

Friedrich Hayek, too, does not seem to consider the possibility that Smith entertained evolutionary ideas about the human species. Hayek[ii] suggests that Charles Darwin got ideas about natural selection from reading Smith, as though understanding of evolutionary economic mechanisms preceded serious consideration of speciation.

It is highly likely that Hume and Smith were acquainted with speciation. Here we suggest that Hume and Smith were proto-Darwinian on human evolution.

The idea of Hume and Smith as discreet speciationists depends on several premises:

- Hume and Smith would have had to intellectually grasp modification, competitive selection, and the evolution of form or species in the general sense. That they grasped such evolutionary mechanisms is amply displayed in their theorizing about morals, property, conventions, social formation, law, government, economics, and culture.

- There would need to have been, before and during their times, thinkers who suggested speciation.

- Hume and Smith would need to have been exposed to such thinking.

Also, our contention would naturally prompt the question: If they were proto-Darwinian, why didn’t they say so plainly?

Scholarship recognizes that Hume and Smith grasped evolutionary mechanisms.[iii][iv] Space does not permit us to touch upon that; we also refrain from elaborating on the causes on account of which Hume and Smith would have been discreet about speciation. We highlight that ideas of speciation were alive before and during the times of Hume and Smith. We note that Hume’s and Smith’s exposure to such ideas was ample.

Why do we care? If Hume and Smith entertained speciation, we, who are accustomed to speciation, may better relate to the larger outlook offered by Hume and Smith. We might see Hume and Smith as more modern than we had thought, or we might see ourselves as more eighteenth century than we had thought. As complete as Coase’s embrace of Smith’s outlook was, it could have been even more so. The outlook teaches understanding of evolutionary mechanisms. Irrespective of whether one takes a theistic view, one is impelled to ponder how things may conduce to some kind of betterment and whether human institutions are self-correcting. Hume and Smith saw healthy correction mechanisms in voluntary affairs but not in government, and thus they generally opposed the governmentalization of social affairs. If Hume and Smith were proto-Darwinian, it would make sense that they saw government—that is, a separate and special set of institutions and practices—as something of a novelty for the human animal. Thus, by considering the proto-Darwinian question we might better understand their anthropology and their political thought.

Speciation Was Alive!

On the heels of the printing press in the fifteenth century, European developments came quickly, including in navigation, exposure to other societies, and scientific attitudes. Figure 1[v] shows a 1555 depiction of unity of plan in animals from Pierre Belon. The image seems designed to suggest relatedness.

Western naturalists came to know anthropoid apes (including bonobos, chimpanzees, and orangutans) under the class of ‘Ourang Outang.’ Here we use the expression Ourang Outang (with capitalization) not to signify what biologists today recognize as an orangutang, but to signify early notions of a bipedal ape with a human visage. We proceed to highlight twelve thinkers (and could add more).

Four Early Englishmen: Tyson, Beeckman, Edwards, and Scotin

The English physician and member of the Royal Society Edward Tyson (1651–1708) published the first systematic study of an ape’s anatomy in Orang-Outang, Sive Homo Sylvestris; or, The Anatomy of a Pygmie (1699). Tyson sought to prove that the pygmies, which classic sources had described as a diminutive race of human beings, were a species of ape so similar to human beings in appearance that they had been mistaken for human beings in folklore: “I shall endeavour to prove in the following Essay…that both the Antients and the Moderns have reputed it to be a Puny Race of Mankind, call’d to this day, Homo Sylvesteris, The Wild Man; Orang-Outang, or a Man of the Wood.”[vi] He reported that his specimen (which was probably a chimpanzee) came from Angola and that merchants who visited him testified that they had seen similar animals in Borneo and Sumatra in the East Indies. Along with his anatomical description, Tyson published an illustration of his specimen[vii] walking with a stick, shown in Figure 2.

Daniel Beeckman was a captain of an English merchant ship, and in 1718 he published a travel narrative of a voyage to Borneo.[viii] Therein Beeckman wrote of Ourang Outangs: “Oran-ootans, which in [the native] Language signifies Men of the Woods: These grow up to be six Foot high; they walk upright, have longer Arms than Men, tolerable good Faces… The Natives do really believe that these were formerly Men, but Metamorphosed into Beasts for their Blasphemy.” Beeckman reported that he had purchased a juvenile Ourang Outang and described its human-like behaviors, providing the illustration shown in Figure 3.

Gérard Jean Baptiste Scotin II (1698–1755) was a printmaker who published an engraving of an ape titled “Chimpanzee” (1738). The description at the bottom of the engraving notes that the specimen came “from Angola, on the Coast of Guinea” and that it “is of the Female kind, is two foot four inches, walks erect, drinks Tea, eats her food & sleeps in a humane way.” The description also notes: “She hath a Capacity of understanding & great Affability.” Scotin’s engraving is shown in Figure 4.

George Edwards (1694–1775) was an English naturalist and member of the Royal Society who published many volumes of descriptions and illustrations of various exotic animals. He described the Ourang Outang under the heading “Man of the Woods” in this Gleanings of Natural History (1751): “This animal, which is one of the first of the genus of Monkies, is supposed to come nearest in outward shape to mind.”[ix] Edwards’s description heavily relied on Tyson’s anatomical description and other travelers’ tales. Edwards published a colored illustration of a Ourang Outang sitting upright with a walking stick shown in Figure 5.

Continental Authors: Bontius, Tulp, Linnaeus, Buffon, Rousseau, and Robinet

Jacobus Bontius (1592–1631) was a Dutch physician in Batavia who described the Ourang Outang as a bipedal great ape with a human visage. His notes and illustrations were posthumously published in 1658 as Historiae Naturalis & Medicae Indiae Orientalis.[x] Bontius described an “Ourang Outang,” or a “Homo Sylvesteris”—“Man of the Woods,” a name originating from the native people of Java. Bontius characterized this Ourang Outang as an animal that could run in a bipedal fashion. One specimen “lacked nothing except human speech.”[xi] Along with his description, Bontius provided a picture of a hairy bipedal female with hair that resembles a lion’s mane and whose face is human, shown in Figure 6.

Another Dutch account of an Ourang Outang came from Nicholas Tulp (1593–1674). In his Observationes Medicae,[xii] Tulp described his specimen (likely a chimpanzee) as having the length of a three-year-old, being very muscular, and having the face of a man, though its nose was sharp and hooked. The locals called the creature an “ourang-outang.”[xiii] Tulp also described it as having many human-like behaviors. Tulp published the illustration shown in Figure 7.

Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) also treated of the Ourang Outang. In the tenth edition of Systema Naturae,[xiv] Linnaeus introduced the order Primates, which he subdivided into four genera: Homo, Simia, Lemur, and Vespertilio—Man, Monkey (or Ape), and Bat. Within that system, Linnaeus[xv] classified the Homo Sylvestris, or Ourang Outang, as Homo Troglodyte, and Linnaeus described Bontius’ Javanese Ourang Outang as an instance of this species. Linnaeus’s grand system of living things provided a place for the Ourang Outang within the scientific study of natural history in the eighteenth century.

Another eminent naturalist to describe the Ourang Outang was George-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707–1788). Buffon was the director of the Jardin du Roi, which he transformed into an institute for biological research. He dedicated much of his intellectual energies towards writing Histoire naturelle, a richly illustrated encyclopedic work that made ideas in natural history widely available to Europe’s literate classes. Smith praises Buffon’s Histoire naturelle in his “Letter to the Edinburgh Review,”[xvi] and Buffon himself presented Hume with two volumes of the work.[xvii][xviii] Buffon described the Ourang Outang, as well as various other apes and monkeys, in the fourteenth volume of his Histoire naturelle: “What I call an Ape is an animal with a flat visage, and without a tail, whose teeth, fingers, nails, and hands, resemble those of the human species, and who also walks upright on its two feet.”[xix] Buffon[xx] described a juvenile Ourang Outang that he observed himself: “The Orang Outang which I saw walked always upright, even when carrying heavy burthens. His air was melancholy, his deportment grave, his movements regular, his disposition gentle, and very different from that of other apes.” The illustration showed a bipedal ape with a human visage holding a walking stick as shown in Figure 8.

According to Buffon, the Ourang Outang occupied an intermediate position between man and lower animal. Buffon insisted on man’s superiority and attributed that superiority to man’s perfectibility and intellectual faculties, which he denied existed in the Ourang Outang.

Buffon understood a ‘species’ as a class of organisms that greatly resembled each other. Buffon’s principal criterion of resemblance was the capability to beget fertile offspring. Yet the necessary and defining feature was something empirically vague, an interior mold within each organism.[xxii] Only organisms with the same interior molds could beget fertile offspring, but Buffon equivocates on defining interior mold.

Buffon argued that climate and sustenance could modify an individual’s interior mold, and those modifications could then be communicated to descendants.[xxiii] Such “degeneration” could induce geographical variation as the individuals have their interior molds gradually modified by the climate and subsistence of their environments. However, Buffon denied the possibility that degeneration could create a new species by transmuting the interior mold of one species into that of another species.[xxiv] He believed (or claimed to believe) that an interior mold was special to each species and that any offspring of different species was infertile because of the differences in its parents’ interior molds. Buffon argued that degeneration could have such effect to make it difficult to recognize two individuals as belonging to a common species.[xxv]

Within his Histoire naturelle, Buffon[xxvi] implies speciation at the end of “On the Degeneration of Species”:

On the other hand, the tigers of America, which we have indicated by the names of jaguars, couguars, ocelots, and margais, though different in species from the panther, leopard, ounce, guepard, and serval, of the Old Continent, are, nevertheless, of the same genera. All these animals greatly resemble each other, both externally and internally… We, therefore, may justly suppose, that these animals had one common origin, and that, having formerly passed from one continent to the other, their present differences have proceeded only from the long influence of their new situation.

Buffon’s “species” talk does not cohere: If species are characterized by unique interior molds, then how is it possible for new and old world animals to be “fundamentally the same” and share the same descent, and yet be “different species” with “real” differences? Buffon seems to suggest speciation, by whatever name.

Buffon may have guessed that, say, a cougar and a leopard could not produce fertile offspring. In fact, here he says that they are “different in species.” Yet, he is saying they had common ancestors. Buffon here implies what biologists call today speciation.

Buffon did not suggest that, in some primeval era, man could have transmuted from another species, but he lit the imagination of the enlightenment reader to the idea of speciation. The only missing step is that the ‘degenerates’ could multiply with each other but not with the organisms from which they degenerated. Buffon was interpreted by Samuel Butler[xxvii] as esoterically suggesting speciation, as has been noted by Arthur Melzer.[xxviii]

In his Discourse on Inequality,[xxix] Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) esoterically discussed the transmutation of species and speculated about natural man’s similarity to Ourang Outangs. At the beginning of the work, Rousseau[xxx] refuses to examine Aristotle’s suggestion that, in the state of nature, man had beastly qualities, but Aristotle never suggested anything of the kind, and Rousseau’s audience most likely knew that. Rousseau’s apparent invocation of Aristotle’s authority was really the fabrication of a mouthpiece for a controversial idea. In “Footnote X,” Rousseau uses travelers’ tales about the Ourang Outang to speculate about natural man’s way of life before society transformed him into a more civilized being.[xxxi] Rousseau’s speculations provoke thought about the similarities, let alone the possible kinship, between natural man and the Ourang Outang.

Rousseau had extensive personal and eventually highly acrimonious interactions with Hume,[xxxii] and Rousseau was engaged by Smith.[xxxii]

In Considerations Philosophiques de la Gradation Naturelle des Formes de L’Etre,[xxxiv] Jean-Baptiste Robinet (1735–1820), a friend and correspondent of Hume’s, emphasized the similarity between man and Ourang Outang. Robinet[xxxv] asserted that the Ourang Outang was an “intermediate species that bridged the gap between ape and man.” The chapter in which he discusses Ourang Outangs and their similarities to human beings begins with an imaginative illustration of an Ourang Outang as an anthropomorphic animal, given in Figure 9. Robinet’s description and illustration readily prompt the thought that man in the state of nature was an Ourang Outang.

Scotland: Monboddo and Kames

James Burnett, Lord Monboddo (1714–99) was a judge in Edinburgh’s Court of Sessions and an early writer on the topic of comparative linguistics. Monboddo wrote at length about the origin of society, especially the origin of language, and about where civil history blends into natural history. In Of the Origins and Progress of Languages (1773–1792)[xxxvi] and Antient Metaphysics (1779–1799),[xxxvii] Monboddo speculated that natural man predated both language and society. Much like Rousseau, Monboddo used available evidence about Ourang Outangs to speculate about natural man’s way of life. In those speculations, Monboddo[xxxviii] explicitly blurred the line between man and Ourang Outang: “there are the Ouran Outangs, who, as I have said, are proved to be of our species by marks of humanity that I think are incontestable… They live in society, build huts, joined in companies attack elephants, and no doubt carry on other joint undertakings for their sustenance and preservation; but have not yet attained the use of speech.” In the first volume of the Antient Metaphysics, Monboddo[xxxix] emphasized the similarity between natural man and the Ourang Outang and even suggested that Ourang Outangs might eventually develop language.

Henry Home, Lord Kames (1696–1782), a close and long-standing friend of Hume and Smith, speculated about the human species in the “Preliminary Discourse concerning the origin of Men and Languages” in his Sketches of the History of Man.[xl] The “Preliminary Discourse” considered whether humanity was one race or many, whether it had one or many origins.[xli] Kames[xlii] discussed Ourang Outangs, noting (incorrectly, as we now know) that even though the animals have the external organs necessary for speaking perfectly, they lacked the mental capacity for language. Kames[xliii] discussed Buffon and Linnaeus at length, especially with respect to the question of what defines a species. As he had done with his four-stages theory, Kames[xliv] argues that, as far back as history goes, “the earth was inhabited by savages divided into many small tribes, each tribe having a language peculiar to itself.”

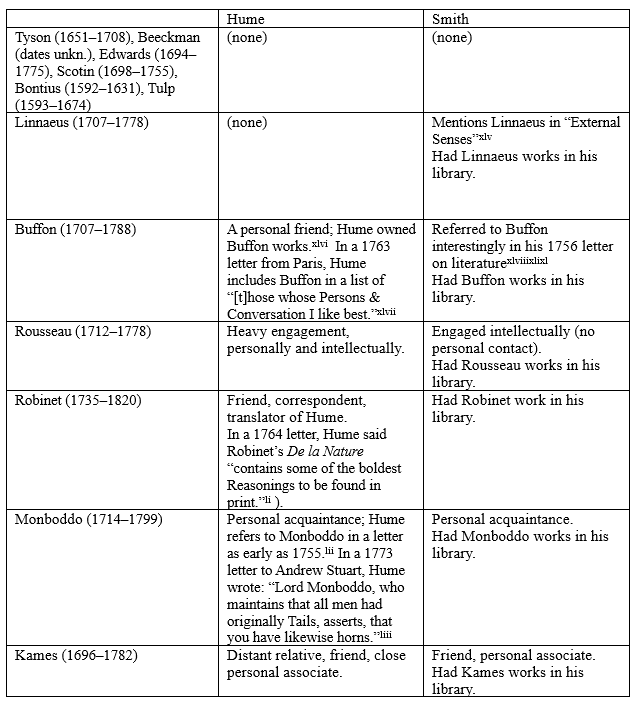

Hume and Smith Were Exposed to Speciation Ideas

If Hume and Smith were discreet transmutationists, they were not discrete transmutationists: Many works with which Hume and Smith were acquainted had developed ideas of descent with modification. The following table reports on signs of such acquaintance.

In their writings on moral rules, religion, culture, economics, jural rules, and government, Hume and Smith amply and pervasively display evolutionary thinking. We find both Lamarckian ideas of adaptive behavior being preserved and natural-selection ideas of survival and perpetuation of the naturally fit. It’s true that Hume and Smith didn’t speculate openly and explicitly about the descent of man (although, in The Natural History of Religion, Hume[liv] writes of “monkeys in human shape,” and he makes suggestive remarks in Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion). To believe that thinkers like Hume and Smith did not think beyond what they made explicit, however, is, as Arthur Melzer[lv] has explained, an obtuseness that set in only after they had passed—an obtuseness to which even Ronald Coase and Friedrich Hayek could fall prey. It makes sense to think that Hume and Smith entertained speciation, since it dovetails so nicely with the rest of their thought, and the idea was familiar to them.

Once we have taken it all in, we ask: What would have kept dedicated truth-trackers like Hume and Smith from entertaining speciation?

[i] Ronald H. Coase, “Adam Smith’s View of Man,” in Essays on Economics and Economists (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994 [1976]), 107–111. Originally published in Journal of Law and Economics (1976).

[ii] Friedrich A. Hayek, The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1988), 24, 146.

[iii] Toni Vogel Carey, “The Invisible Hand of Natural Selection, and Vice Versa,” Biology and Philosophy 13, 427–442 (1998).

[iv] Toni Vogel Carey, “The ‘Sub-Rational’ in Scottish Moral Science,” Journal of Scottish Moral Philosophy 9, no. 2: 225–238 (2011).

[v] Pierre Belon, L’Histoire de la Nature des Oyseaux (Prevotius: Benedictus, 1555), Link.

[vi] Edward Tyson, Orang-Outang, Sive Homo Sylverstris; Or, the Anatomy of a Pygmie (London: Thomas Bennet and Daniel Brown, 1699), 1, Link.

[vii] Edward Tyson, Orang-Outang, Sive Homo Sylverstris; Or, the Anatomy of a Pygmie (London: Thomas Bennet and Daniel Brown, 1699), Link.

[viii] Daniel Beeckman, A Voyage to and from the Island of Borneo in the East Indies (London: T. Warner and J. Batley, 1718), Link.

[ix] George Edwards, Gleanings of Natural History (London: Royal College of Physicians, 1758), 6, Link.

[x] Jacobus Bontius, Historiae Naturalis & Medicae Indiae Orientalis, ed. Gulielmus Pisonis (Amsterday: Ludvicus and Danielis, 1658), Link.

[xi] Jacobus Bontius, Historiae Naturalis & Medicae Indiae Orientalis, ed. Gulielmus Pisonis (Amsterday: Ludvicus and Danielis, 1658), 85, Link.

[xii] Nicholaas Tulp, Observationes Medicae (Lugdunum Batavorum: Andr. Dyckhuysen and J.A. Langerak, 1716), Link.

[xiii] Nicholaas Tulp, Observationes Medicae (Lugdunum Batavorum: Andr. Dyckhuysen and J.A. Langerak, 1716), 270, Link.

[xiv] Carolus Linnaeus, Systema Naturae, Tomus I. Ed. X (Vindobonae: Ioannis Thoma, 1767), Link.

[xv] Carolus Linnaeus, Systema Naturae, Tomus I. Ed. X (Vindobonae: Ioannis Thoma, 1767), 34, Link.

[xvi] Smith’s letter on literature is contained in Essays on Philosophical Subjects, edited by D.D. Rapael and A.S. Skinner (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980).

[xvii] David Hume, The Letters of David Hume, Volume II 1766–1776, ed. J.Y.T. Grieg (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1932), 82.

[xviii] Adam Smith, Essays on Philosophical Subjects, edited by D.D. Rapael and A.S. Skinner (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980), 248.

[xix] Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, Buffon’s Natural History, vol. 9, trans. James Smith Barr (London: H.D. Symonds, 1797), 108, Link.

[xx] Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, Buffon’s Natural History, vol. 9, trans. James Smith Barr (London: H.D. Symonds, 1797), 158, Link.

[xxii] Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, Histoire Naturelle, Générale et Particulière, Tome Second (Paris: L’Imprimerie Royale, 1750), 258, Link.

[xxiii] Jacques Roger, Buffon: A Life in Natural History, trans. Sarah Lucille Bonnefoi (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1997), 316.

[xxiv] Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, Histoire Naturelle, Générale et Particulière, Tome Quatrième (Paris: L’Imprimerie Royale, 1753), 391, Link.

[xxv] Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, Histoire Naturelle, Générale et Particulière, Tome Neuvième (Paris: L’Imprimerie Royale, 1761), 320–21, Link.

[xxvi] Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, Buffon’s Natural History, vol. 10, trans. James Smith Barr (London: H.D. Symonds, 1797), 20–21, Link.

[xxvii] Samuel Butler, Evolution, Old and New (London: David Bogue, 1882), 81–83, Link.

[xxviii] Arthur M. Meltzer, Philosophy Between the Lines: The Lost History of Esoteric Writing (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 223.

[xxix] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men,” in Roussea: ‘The Discourses’ and Other Early Political Writings, ed. and trans. Victor Gourevitch (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 111–222.

[xxx] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men,” in Roussea: ‘The Discourses’ and Other Early Political Writings, ed. and trans. Victor Gourevitch (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 134.

[xxxi] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men,” in Roussea: ‘The Discourses’ and Other Early Political Writings, ed. and trans. Victor Gourevitch (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 205–207.

[xxxii] David Hume, “Hume’s Manuscript Account of the Extraordinary Affair Between Him and Rousseau,” Econ Journal Watch 18, no. 2: 278–326 (2021 [1766]), Link. Recounted in. Daniel B. Klein, “To Tolerant England and a Pension from the King: Did Hume Subconsciously Aim to Subvert Rousseau’s Legacy?” Econ Journal Watch 18, no. 2: 327–350 (2021), Link. Treated by.

[xxxii] Daniel B. Klein, The Spirit of Smithian Laws (CL Press, 2025), ch.9, Link.

[xxxiv] Jean-Baptiste Robinet, Considerations Philosophiques de la Gradation Naturelle des Formes de L’Etre (Paris: Charles Saillant, 1768), Link.

[xxxv] Jean-Baptiste Robinet, Considerations Philosophiques de la Gradation Naturelle des Formes de L’Etre (Paris: Charles Saillant, 1768), 151, Link.

[xxvi] Lord James Burnett Monboddo, Of the Origin and Progress of Language, Vol. I. (Edinburgh: A. Kincaid & W. Creech, 1773), Link.

[xxvii] Lord James Burnett Monboddo, Ancient Metaphysics, Volume Fourth (Edinburgh: Bell and Bradeute, 1795), Link.

[xxxviii] Lord James Burnett Monboddo, Of the Origin and Progress of Language, Vol. I. (Edinburgh: A. Kincaid & W. Creech, 1773), 289, Link.

[xxxix] Lord James Burnett Monboddo, Ancient Metaphysics, Volume Fourth (Edinburgh: Bell and Bradeute, 1795), 106–107, 123, Link.

[xl] Henry Home, Lord Kames, Sketches of the History of Man, Volume I (Edinburgh: W. Creech, 1774), Link.

[xli] Ronald L. Meek, Social Science and the Ignoble Savage (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), 155–56.

[xlii] Henry Home, Lord Kames, Sketches of the History of Man, Volume I (Edinburgh: W. Creech, 1774), 40–41, Link.

[xliii] Henry Home, Lord Kames, Sketches of the History of Man, Volume I (Edinburgh: W. Creech, 1774), 8–9, Link.

[xliv] Henry Home, Lord Kames, Sketches of the History of Man, Volume I (Edinburgh: W. Creech, 1774), 38, Link.

[liv] David Hume, The Natural History of Religion, with an introduction by John M. Robertson (London: A. And H. Bradlaugh Bonner, 1889 [1757]), Link.

[lv] Arthur M. Meltzer, Philosophy Between the Lines: The Lost History of Esoteric Writing (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2014).