The Enduring George Will

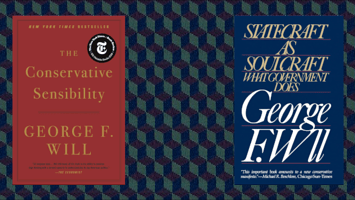

Klein assesses George Will’s two most renowned books, 36 years apart, Statecraft as Soulcraft (1983) and The Conservative Sensibility (2019), finding some changes upon an underlying continuity—rather like the two levels of human nature exposited by Will 1983.

In 1983, George Will published Statecraft as Soulcraft: What Government Does. Thirty-six years later, in 2019, he published The Conservative Sensibility. Both books concern themselves with virtue and the higher things. Both recognize an enduring human nature, a degree of malleability of human beings, and the role of government in malleating them. Between the two books, the drift changes, but I do not see deep conflict between the two books.

Different circumstances account for some of the differences between the two books. In 1983, with Ronald Reagan in the Oval Office and his administration at the anvil, Will emphasized malleability and the potential upside of the government’s role, saying “now is a good time to tidy up the idea of conservatism” (p. 12). He wrote: “Talk matters… We are, to some extent, what we and our leaders—the emblematic figures of our polity—say we are” (p. 159). The following quotation captures the main idea of Statecraft as Soulcraft:

My point, remember, is not just that statecraft should be soulcraft. My point is that statecraft is soulcraft. It is by its very nature. Statecraft need not be conscious of itself as soulcraft; it need not affect the citizens’ inner lives skillfully, or creatively, or decently. But the one thing it cannot be, over time, is irrelevant to those inner lives. (p. 144)

Statecraft as Soulcraft began as the 1981 Godkin Lectures delivered at Harvard University; the speaker delivered a message that goes down well with the best and brightest.

By 2019, after a parade of leaders emblematizing God knows what, things had changed a great deal. With The Conservative Sensibility, Will presents a book “written at a moment when conservatism is again a persuasion without a party” (p. xxxiii); he sees human nature as not so malleable, emphasizes natural rights, and emphasizes the actual downside, for moral character, of the hammers of government. I abbreviate Statecraft as Soulcraft as SaS and use past tense when quoting it, and The Conservative Sensibility as TCS and present tense.

Whereas TCS is bulky and discursive, SaS is compact and pithy. How about this?: “Socialism is an expression of the disease for which it purports to be the cure” (SaS, p. 119).

Both books take “conservatism” as the name of Will’s creed, but in TCS, first clarifying it as American, as opposed to European conservatism (the two are said to have “little in common,” p. xxiii), Will says American conservatism is a sort of classical liberalism.

Will notes that the expression, classical liberalism, is still embraced by “a few intellectually fastidious people.” I, for one, am not so sure that the concept of fastidiousness—taking care to the point of excess—is operative in the domain of intellect, especially as concerns ideas most central to one’s outlook.

At any rate, the answer that TCS gives to the question, “What do you seek to conserve?,” is concise: “We seek to conserve the American Founding” (p. xvii). “American conservatives are the custodians of the classical liberal tradition” (p. xxiv). I would propose “conservative liberalism.”

But the good tradition has been besieged: “Progressivism represents the overthrow of the Founder’s classical liberalism” (TCS, p. xxv). The epic struggle is between the two: “Broadly speaking, there are conservative and progressive conceptions of human nature, conservative and progressive assumptions about how history unfolds, and conservative and progressive expectations about how the world works” (TCS, p. xxx). TCS says that it aims to explain “the Founders’ philosophy, the philosophy that the progressives formulated explicitly as a refutation of the Founders, and the superiority of the former” (p. xxiii).

That epic struggle is not central in SaS. There the mission is to tidy up conservatism. Indeed, the tidying serves not only conservatism but, more broadly, “the liberal-democratic political impulse,” supposedly shared by Ronald Reagan and Franklin D. Roosevelt (SaS, p. 23).

Upon fair inspection (which is something I failed to give in 2005), SaS is not much at odds with the best classical liberalism. Will freely said: “Conservatives…believe that the public interest is produced by the spontaneous cooperation of individuals making arrangements in free markets” (SaS, p. 22). SaS is not concerned with different liberalisms, and progressivism is little mentioned. To improve conservative thought, Will, at the outset, warned: “I must commit political philosophy” (p. 15).

If the passage above about statecraft as soulcraft rubs you the wrong way, the rub may be less real than apparent, and it probably arises from “soulcraft.” The word is arresting. But it is inapt. All Will means by “statecraft as soulcraft” is that government “conditions the action and the thought of the nation in broad and important spheres of life.” It influences “sentiments, manners, and moral opinions” (p. 19). That is true. And its truth is still too little pursued. Yet I regret that the lesson was couched in terms of “soulcraft,” which goes overboard with respect to the affected object (“soul”) and with respect to the affecting (“craft”). James Madison crafted many fine sentences, but Will knew that government is no craftsman. To define, or redefine, “soulcraft,” Will wrote:

Statecraft as soulcraft should mean only a steady inclination, generally unfelt and unthought. It should mean a disposition, in the weighing of political persons and measures, to include consideration of whether they accord with worthy ends for the polity. Such ends conduce—that word is strong enough—to the improvement of persons. (SaS, p. 94)

And he assured the reader that he was not seeking a craftsman: “A particular institution charged with the routinized planning of virtue, the way the Federal Highway Administration plans highways, would be ominous and would deserve the ridicule it would receive” (SaS, p. 95).

“Soulcraft” aside, it is only at isolated moments that SaS seems at odds with conservative liberalism. One example is when Will wrote that “real conservatism…should challenge the liberal doctrine that regarding one important dimension of life—the ‘inner life’—there should be less government—less than there is now, less than there recently was” (SaS, p. 24). That sounds favorable to government being more activist in the inner lives of individuals. The Will of 2019 most definitely rejects government being more activist in the inner lives of individuals.

An aspect of the enduring George Will is his contemplation of the ancients versus the moderns. In TCS he puts the matter as follows:

The ancients had asked, What is the highest attainment of which mankind is capable and how can we pursue this? Hobbes and subsequent moderns asked, What is the worst that can happen and how can we avoid it? (TCS, p. 19)

In SaS, Will was suggesting that government take a more active role in promoting the higher things. While extolling Edmund Burke, he drove a wedge between Burke and his friends David Hume and Adam Smith, by insinuating (unjustly) that they – Hume and Smith – advised men to satisfy themselves with lower things, like comfort, convenience, and entertainment (SaS, pp. 32, 34, 134). What’s more, Will insinuated something similar about the American Founding:

I shall not disguise, or delay deploying, the implication of my argument. It is that liberal democratic societies are ill founded. If true, this is an especially melancholy bulletin for the most thoroughly liberal democratic nation, the United States. Aristotle said about reasoning that a little mistake at the beginning becomes a big mistake at the end. In politics, a big mistake at the founding can bring on the end of what was founded. (SaS, p. 18)

And Will even suggested that the Founders had acted rashly:

But prudent political thinkers have more worries than appear prominently in Madison’s philosophy. The American Founders talked almost exclusively about institutional arrangements and the sociology of the factions presupposed by the institutional arrangements. They talked little about the sociology of virtue, or the husbandry of exemplary elites – the “best patterns of the species” of which Burke wrote. Perhaps this is because they assumed that the necessity of constant, systematic concern for the cultivation of character was plain as a pikestaff; perhaps it is because the continuous existence in America of an aristocracy of public-spirited talents was assumed. Rashly. (SaS, p. 40)

Elsewhere in SaS, Will wrote of “Madison and the other Founders” having a “conception of the politically relevant human nature [that] was too stark, too unidimensional in its emphasis on self-interestedness” (SaS, p. 67). Even in 1983 Will expressed misgivings of “filial impiety” (SaS, p. 168).

In TCS, Will speaks of SaS. He justly reaffirms the main idea, while, alas, continuing to use “soulcraft:”

[S]oulcraft—shaping the morals and manners of its citizens—is not merely something the government can or should choose to do. Rather, it is something government cannot help but do. It may not be done competently or even consciously, but it is not optional. Legal regimes, and the commercial and educational systems that the laws create and sustain, have consequences on the thinking, behavior, expectations, desires, habits, and demands—cumulatively, on the souls—of the citizenry. (TCS, p. 227)

However, Will confesses an error in SaS, and offers a correction: “Another of the book’s themes was quite wrong. It was that the American nation was ‘ill-founded’ because too little attention was given to the explicit cultivation of the virtues requisite for the success of a republic” (TCS, p. 228).

Will then points to the great school of virtue: “[T]he nature of life in a commercial society under limited government is a daily instruction in the self-reliance and politeness—taken together, the civility—of a lightly governed, open society… Politeness is woven into the society’s interactions, and over time, through endless iterations, it produces a fabric of civility… Therefore, a commercial republic—a market society—promotes the habits (virtues) of politeness and sociability” (TCS, p. 228). From the wide-angle lens, we see that the Founders did fashion government to best condition “sentiments, manners, and moral opinions.”

Thus, in TCS, Will conveys a progression of authorial sentiment: When writing SaS, he had looked too much for some kind of governmental tutoring, and suggested that the American Founders had neglected this important aspect of governance. Now, in TCS, the heroes are none other than the American Founders. In TCS, Hume and Smith are mentioned cordially, while Burke ebbs and, curiously, comes in for some ill treatment (TCS, pp. xxvi, 54–55).

Will has not abandoned the notions that government has moral consequences and those consequences should be understood and counted in our estimations of policies and politicos. It’s just that in TCS he expresses a different opinion as to how that is best done in the American context: Get back to the Constitution and reduce the governmentalization of social affairs. “[T]he Constitution was designed to encourage particular habits of thinking and acting. From visible habits we make inferences as to invisible attributes of the soul. Therefore statecraft, as the Founders understood it, is soulcraft” (TCS, p. 236).

Will writes: “[A] capitalist society does not merely make us better off, it makes us better” (TCS, p. 233). Better than what?, one might ask. Better than what happens under advancing governmentalization of social affairs: “Government can damage associational life, and big government can do big damage” (TCS, p. 233). Will writes at length about the evil moral consequences of systemic statism. In 1983, Will was tidying up conservatism. Now his salient posture is opposition to big government, invoking the American Founding.

The change is also seen in how a certain idea is treated in SaS versus TCS, namely, human nature. In SaS, Will wrote: “The most politically important idea of the last two centuries is the idea that human nature has a history” (SaS, p. 56). There, in SaS, Will takes the view that part of the essence of human nature is our being acculturated animals. Cultural influences play their part in forming within each individual a “Second Nature” (the title of a chapter of SaS). The second nature is “a conscious recovery of, and enhancement of, a portion of the first nature, the ‘given’ in human beings” (SaS, p. 68). The two natures interpenetrate one another. Will suggested that government ought to arouse and inspire the morality of aspiration (from Lon Fuller, who got it from Adam Smith), and even condition it by extending the morality of duty, meaning here legal rules (SaS, p. 82). In TCS, however, Will’s stance on government as tutor has changed, as has his view on human nature, which becomes less malleable. Without calling attention to the words I just quoted from SaS page 56, he writes in TCS: “Conservatives are implacably hostile to the Idea that human nature has a history” (TCS, p. 527).

Governmentalization becomes more unqualifiedly debasing and degenerative: “[G]overnment itself has become inimical to the virtues essential for responsible self-government. Government has become inimical because it fosters both dependency and uncivic aggressiveness in attempting to bend public institutions to private factional advantage” (TCS, p. 527).

Also, with the emphasis on human nature comes a greater emphasis on natural rights. Indeed, Will explains that the conservative hostility to the idea that human nature has a history “is implacable because the idea is subversive of government based on respect for natural rights” (TCS, p. 527). As for me, I like natural rights fine, but regret how much TCS goes in for political consent.

In TCS, Will gives a not-so-satisfying chapter to “Conservatism without Theism.” He calls himself “an amiable, low-voltage atheist” (TCS, p. 479). He says: “Theism is an optional component of conservatism” (p. 486). He provides something of a definition of atheism and distinguishes atheism from agnosticism (pp. 505–506). Will tries to express a spiritualism without God, but he falls short of saying that benevolent monotheism provides the template for proper ethics. Properly done, ethics utilizes the idea “that there is an unseen order, and that our supreme good lies in harmoniously adjusting ourselves thereto,” something which our amiable atheist says lacks evidence (p. 505).

The two books, SaS and TCS, provide a rich encounter with the enduring George Will, and, through him, with the goodness of the American Founding and the essence of the American drama. TCS is occasionally autobiographical. It should endure as one of the great testimonies of an American sage.

In retrospect, SaS, all in all—though the term “soulcraft” should be dumped altogether—is a book to learn from, enjoy, and embrace—once clarified and a few moments excused. (In 2017 I published something with the aim of atoning for my 2005 unfairness.) The book SaS was right when it said: “The idea that governments should be neutral in major conflicts about social values is only slightly more peculiar than the idea that government can be neutral” (SaS, 20). Along related lines, I love this one:

A famous economist, who has a Nobel Prize and (what is almost as much fun) a regular column in Newsweek, recently became so exasperated with me (for some deviation from laissez-faire orthodoxy) that he wrote a stiff note. He said that he likes what I write—except when I write about economics. I am too exquisitely polite to have replied that I like what he writes—except when he writes about politics, and he rarely writes about anything else. (SaS, p. 126)

But SaS is superseded by TCS, which provides a fuller and better testimony. Here are words from the end of TCS:

[T]he American Founding was a luminous moment, a hinge on which world history turned, because of the ideas it affirmed and then translated into constitutional institutions and processes… Can we get back, not to the conditions in which we started, but to the premises with which we started?… We cannot escape the challenge of living by the exacting principles of our Founding, so we should beat on, boats against many modern currents, borne back ceaselessly toward a still-useable past. (TCS, p. 538)