The Nativist Snap

If the US hadn’t opened its doors to immigration in the 1960s, there would be eighty million fewer Americans today, an utter disaster given the looming, global underpopulation crisis.

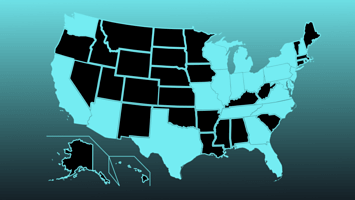

80 million fewer immigrants is the equivalent of losing these 30 states (in black) worth of people.

What if a nativist snapped his fingers, Thanos-style, and reversed the last six decades of immigration to the United States? It would mean the erasure of eighty million immigrants and their children.

Human beings are hardwired to comprehend small numbers, the number of people in our hunting party, extended family, or immediate tribe. Eighty million is so large a number as to be beyond ordinary comprehension; if it were eight or eight hundred million it would have the same mental effect.

Eighty million people is more than the combined population of thirty states. You could empty every state from Wyoming (#50) through Colorado (#21) and still have a few hundred thousand people to spare before hitting eighty million total population.

Eighty million people dwarfs the ~1.3 million Americans killed in all US wars combined. Immigration restrictionism is a more powerful tool for obviating Americans than any bomb or bioweapon yet devised. Hateful, ignorant ethno-nationalists are a greater threat to the future of the American nation than any foreign foe we have ever faced.

But comprehending the sheer immensity of eighty million people only gets us part way to appreciating just how devastating a blow their loss would be to American prosperity and power. That’s because immigrants punch above their weight by nearly every positive measure of social and economic achievement.

Immigrants and their children are only ~25% of the US population. Yet 43% of all Fortune 500 companies have first or second generation immigrant founders and more than half of America’s Nobel Prize winners were born abroad. The US has as many immigrant inventors as the next twenty-six countries combined, or nearly eight times more than the distant number two on the list, Germany! Without immigrants, America would be a middling what-if cautionary tale instead of a dominant presence in the global technology sector.

All that innovation results in economic growth. A single category of immigrants—those holding H-1B visas and comprising less than 1% of the total population—was responsible for as much as 20% of all productivity growth in the US between 1990 and 2010. Economists complain about the “Great Stagnation” in American productivity growth since the 1970s; but without millions of immigrant inventors and entrepreneurs, it might have been called the “Great Plateau.”

These losses would not have been mere locational transfers of productivity. If that were so, America’s loss would simply have been other countries’ gain and net human growth would have been similar. But America attracts immigrants in part because we still enjoy world-pacing social, industrial, and educational infrastructure. Our university system is the envy of the world, our research labs are extensive and well-financed, and—despite the worst efforts of nativists—we remain far more welcoming to immigrants than peer nations like Japan or China.

Which means that preventing eighty million immigrants from coming to America since 1965 would have created what economists call deadweight loss. It would have meant scientists, engineers, teachers, entrepreneurs, and workers of every kind not being able to as fully maximize their latent human potential.

To provide just one example, consider the story of Katalin Karikó. You might have heard her name mentioned as the mother of mRNA technology; her research is ultimately responsible for the two most effective Covid-19 vaccines. But you might not be aware that she is an immigrant. Decades before she played a vital role in mitigating the worst global pandemic of our lifetimes, her work was nearly stymied by her inability to get a visa for her husband to join her from Hungary. And then her original visa sponsor, jealous that she took another job, attempted to have her deported.

Without access to American research universities and venture capital, it is improbable that her pioneering work would have been completed. The loss to net human flourishing from this single, blocked immigrant--albeit a particularly extraordinary one--is unfathomable. And it is impossible to tell which of the next eighty million immigrants to arrive here will be the next Karikó, Jeff Bezos, Sergey Brin, or any of the other first or second generation immigrants who have made the world happier, healthier, and more prosperous. Every immigrant is a lottery ticket for which the prize is American success and global benefit; the upside is limitless and the floor is actually quite high given that immigrants are more likely to start businesses and less likely to commit crimes than the native-born.

But it is particularly important at this moment in time that America not slam shut the door on immigration. Immigrants have always been a crucial source of American vitality and prosperity, but the world is now confronting a worsening underpopulation crisis. And as fewer children are born, especially in economically developed countries, the median age has climbed. In the US, the median age has climbed from 22.9 years in 1900 to 38.1 years in 2019.

That is a problem because our social institutions are not prepared to deal with this combination of population decline and rising median age. Given that most social security programs are dependent on a large, growing workforce, the changing ratio of workers to retirees and other non-workers will lead to a wave of political infighting over benefits cuts and tax increases. Fewer workers means global economic productivity gains will stagnate, a precondition for the kinds of political unrest that can destabilize previously functional democracies.

Yet as concerning as America’s aging trend is, it has been significantly alleviated by immigration. By contrast, countries without significant immigration flows have gone prematurely grey, like in Japan where the median resident is 48 years old. Indeed, Japan’s story is instructive given that its median age in 1950 was 22.3 years, meaning that despite being younger than the US within living memory, it is now fully a decade older. If it were not for immigration, America’s population trends over the last half century would have resembled Japan’s.

Japan’s gerontocratic decline is a cautionary tale. It is commonplace for American politicians to worry about the geopolitical rise of China, but readers of a certain age will recall the era of peak American paranoia towards Japan. In the 1980s and early 1990s, it was all the rage among American policymakers to worry about Japanese dominance in tech and international business. Novelist Michael Crichton followed the success of his bestselling Jurassic Park with a book titled Rising Sun, featuring a nefarious Japanese conglomerate entangled in corporate espionage, political corruption, and even murder most foul.

Neither Crichton’s novel nor those broader fears have aged well. Weighted down by a shrinking workforce and rising government spending, Japan’s economic growth has stagnated. Japan has one of the most stringent immigration regimes in the world, preventing migrants from alleviating its economic and population woes. That stagnation has, in turn, ushered in a recrudescence of far right nationalist politics, as people retreat into their nostalgia for a time of Japanese ascendancy. Japan is a scale model of what the US should expect from population decline and restrictive immigration policies. Let’s not learn that lesson the hard way.